Column Mapping

Column mapping allows you to configure how your records should be stored in HBase for maximum performance and efficiency. You define the column mapping in JSON format in a data-centric way. Kite stores and retrieves the data correctly.

A column mapping is a JSON list of definitions that specify how to store each field in the record. Each definition is a JSON object with a source, a type, and any additional properties required by the type. The source property specifies which field in the source record the definition applies to. The type property controls where the source field’s data is stored.

The most common type is column, which stores the source field in a cell. HBase cells are identified by column family and column qualifier, which are the two required properties for column. For example, here is a single column definition for a timestamp field, with a family m and a qualifier ts.

1 |

{"source" : "timestamp", "type" : "column", "family" : "m", "qualifier" : "ts"}

|

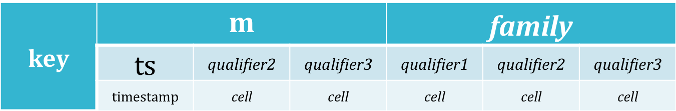

The identifiers are stored repeatedly in the dataset, so it’s best practice to keep the names short, but long enough to provide context. The table structure in the data store is similar to this:

Each source field should have a corresponding column definition in the complete mapping. Below is an example of a complete column mapping for a simple user record.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

[

{"source" : "email", "type" : "column", "family" : "u", "qualifier" : "mail"},

{"source" : "first_name", "type" : "column", "family" : "u", "qualifier" : "fname"},

{"source" : "last_name", "type" : "column", "family" : "u", "qualifier" : "lname"},

{"source" : "created_at", "type" : "column", "family" : "u", "qualifier" : "ts"}

]

|

Mapping types

There are five mapping types: column, counter, keyAsColumn, key, and version.

Column mapping

The column type maps a value to a single cell identified by the family and qualifier properties.

The value in a cell is not necessarily a primitive type. It can be a more complex type, such as an entire Avro record or table.

Counter mapping

The counter is similar to column, but can be incremented using HBase’s atomic increment. The field data is stored in a cell identified by the required family and qualifier properties, and the source field for a counter must be an integer or a long. A good example is user visits to a website. Every time the user visits the site, the site increments the user’s visit counter.

1 |

{"source" : "visits", "type" : "counter", "family" : "u", "prefix" : "visits"}

|

HBase increments the counter atomically. If there are two visits at the same time, it guarantees that they will not be mistakenly combined into one, but will be counted separately. The sequence is

- read the value

- increment by one

- store the value

Even if another user reads the value and begins an edit in between, HBase guarantees that the information is stored correctly (that is, your change will not overwrite changes made concurrently).

Key mapping

HBase stores everything by a unique key for each record, made from the record’s data. For example, users might be stored by their e-mail address. You could use column to store the e-mail in a cell, but it is already stored in key for the record. Kite can retrieve the email value from the key. It doesn’t have to be stored a second time in the data.

1 |

{"source" : "email", "type" : "key"}

|

In Kite, we define the key using a partition strategy. For the above e-mail mapping, you would need to use a partition strategy that includes the e-mail like this.

On the file system side, the keys overlap. That’s how we group things together into common buckets that have properties such as Year, Month, and Day for all of the events in the same bucket.

HBase does that partitioning for you: it groups items together based on unique keys. If it needs to, it will split the file when it gets to be of sufficient size. The keys don’t point to a group. The keys point to an individual record, and then groups are made from those keys, dynamically.

What you want to do is take your unique identifiers and store those as your keys.

Complex record mapping

Use keyAsColumn to store a complex record or a hash map in a particular column family.

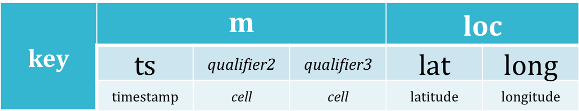

For example, if you store locations made of a latitude, longitude pair, you could store the location record in the loc family using the following mapping.

1 |

{"source" : "location", "type" : "keyAsColumn", "family" : "loc"}

|

1 |

location = {"lat" : 12.34, "long" : 128.14}

|

Kite uses the family property you provide as the column family, but uses the names of the individual elements of the column record to name the qualifiers. The family property is required.

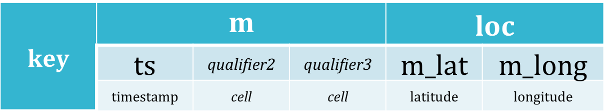

This also supports an optional prefix for the qualifiers. For example, you could add the prefix “m_” to your column definition for easier identification.

1 |

{"source" : "location", "type" : "keyAsColumn", "family" : "loc", "prefix" : "m_"}

|

A keyAsColumn source field must be a record or a map. The difference when using a map is that you don’t know the names of the qualifiers in advance. Keys is used as the qualifiers, and the values is stored in the cells.

The fields in the record or map can themselves be complex objects.

Version mapping

The occVersion mapping is a special type of counter. It’s the only counter allowed on the record. Counters use atomic updating, where the increment is handled inside the database. Version, being the version of the record, is the only counter allowed. It has an automatic storage system that the user cannot control. You can access the version on the record itself, but you have no opportunity to change the value.

1 |

{"source" : "record_version", "type" : "occVersion"}

|

The version is incremented every time you “put” the record. This provides a concurrency guarantee. You update the record, store all the data, then update the version with an atomic operation. It uses OCC (Optimistic Concurrency Control). If you begin an edit based on version 6, it checks to see if it is still at version 6 before allowing you to store the record. If someone else has changed it in the interim, you get a rejection message. Typically, such collisions are rare, so working under the assumption that such a collision won’t occur is the most efficient mode of operations most of the time.